These are the voyages of five Scottish figures that made it their business to explore strange new worlds, to seek out new life and new civilizations, and to boldly go where no one had gone before.

The Scots do seem to crop up everywhere, within every land and culture, with many having made a significant contribution. The following individuals all made such a journey, and all have left some sort of legacy.

John Muir (1838-1914)

Muir was a pioneer of conservation and ‘Father of the National Parks’.

Muir was a pioneer of conservation and ‘Father of the National Parks’.

Born in Dunbar, East Lothian, Muir’s family left for a new life in Wisconsin, USA, when he was only eleven. Here Muir developed a passion for all thing botanical and natural, and though his university credits indicate he never actually graduated, but studied a diverse range of topics.

After his eclectic education, he explored widely in the US and Canada, writing of his experiences and discoveries. In September 1867, Muir undertook a walk of about 1,000 miles from Indiana to Florida, which he recounted in his book, A Thousand-Mile Walk to the Gulf. He also explored Yosemite Valley and was integral to its protection.

Muir was the founder of the US National Park system, forming the Sierra Club to protect the environment, and has parks and buildings named after him both in Scotland and the US.

The John Muir Trust now exists to protect the UK’s wild places. The trust owns and manages six estates in Scotland (c 47 000 acres): Knoydart, Sconser, Strathaird and Torrin (Isle of Skye), Schiehallion (Perth & Kinross) and Sandwood in Sutherland.

William Spears Bruce (1867-1921)

Although technically not Scottish, he was the son of a Scottish medic, studied at Edinburgh University and owned a house in Portobello, so let’s claim him as our own. Spears was an oceanographer and Polar Explorer, famously advising Robert Falcon Scott that his supply stations were too widely spaced. Hence Scott’s failed attempt to reach the South Pole.

Although technically not Scottish, he was the son of a Scottish medic, studied at Edinburgh University and owned a house in Portobello, so let’s claim him as our own. Spears was an oceanographer and Polar Explorer, famously advising Robert Falcon Scott that his supply stations were too widely spaced. Hence Scott’s failed attempt to reach the South Pole.

Spears was one of the first to explore the Antarctic, discovering Coats Land a 240km stretch of the coast of the Antarctic continent. It was named after the Paisley thread-manufacturing family to which the main financial backers of the expedition belonged.

Spears also founded the Scottish Oceanographical Society, the Scottish Ski Club and Edinburgh Zoo. For the latter, he nabbed some penguins from his forays in the Antarctic.

Dr John Rae (1813-1893)

John Rae discovered the final navigable link in the Northwest Passage (a sea route in the Arctic joining the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean) – but has been treated unfairly in the history books, with this discovery being credited to Sir John Franklin and Sir Robert McClure.

Born at the Hall of Clestrain, Ophir, in Orkney, Rae first studied medicine at Edinburgh and then went into the service of the Hudson’s Bay Company as a surgeon on board The Prince of Wales. This was bound for the North Atlantic and Arctic. He worked as a surgeon and general trader in James Bay, Canada, and effectively learned the survival techniques and ways of the local Inuit and Cree Indians.

Rae mapped hundreds of uncharted Canadian coastal miles and in 1948 undertook an expedition to find out what happened to the ill-fated Royal Navy Expedition (lead by Sir John Franklin) that had set out to discover the Northwest Passage. He found that their ship had been trapped by ice and many had died from illness, but the local Inuit people filled-in the blanks. Cannibalism had been a last resort for these unfortunate men to try to survive.

Exploring a further thousand miles of this uncharted coastline in the area where he searched for Franklin, Rae made a crucial discovery. What was thought to be ‘King William Land’ was actually an island, and that the strait separating it from the mainland (’Rae Strait’ ) was the last uncharted link in the Northwest Passage.

On his return, his news of what happened to the Franklin Expedition was shocking and unacceptable to Victorian England. Lead by Franklin’s wife, efforts were made to discredit Rae, and he was not credited with the discovery. Instead, Franklin was.

Fatal Passage – The Untold Story of John Rae the Arctic Explorer Who Discovered the Fate of Franklin’ by Ken McGoogan.) www.orcadian.co.uk/books/index.html

Basil Hall (1788-1844) ((http://web.archive.org/web/20060507004609/http://www.electricscotland.com/history/other/hall_basil.htm))

Proved that the pen is mightier than the sword by writing books and keeping journals that give a wonderful insight to the world during his lifetime.

Proved that the pen is mightier than the sword by writing books and keeping journals that give a wonderful insight to the world during his lifetime.

Born In Edinburgh, Hall joined the Navy and quickly reached the rank of Captain. Commanding a number of vessels involved with scientific and diplomatic expeditions, these missions brought him into contact with interesting people and places.

In Spain he saw the dying Sir John Moore being carried from the battlefield in Corunna and in 1817 had an audience and interview with Napoleon. In 1824 he spent time at the home of Sir Walter Scott, writing about the author’s domestic life.

When he left the navy, he and his wife continued to travel, with Hall writing many informative and memorable books about his experiences, as well as many published scientific papers:

- The Fragments of Voyages and Travels

- Account of a Voyage of Discovery to the West Coast of Corea and the Great Loo-Choo Island in the Japan Sea

- Winter in Lower Styria

- Extracts from a Journal Written on the Coasts of Chile, Peru and Mexico

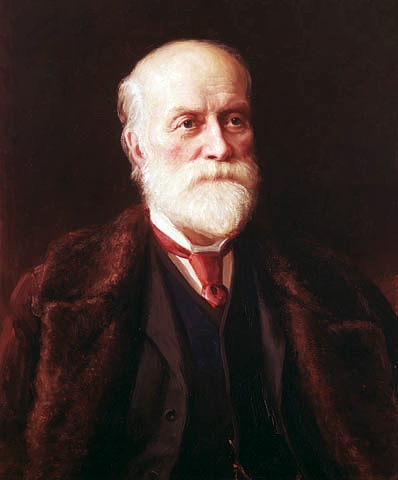

Sir Sandford Fleming (1827-1915)

Born in Kirkcaldy, Fleming was an engineer and an inventor, but is perhaps best known as ‘The Time Lord’, having proposed the creation of Standard Time, and worldwide time zones.

In fact, this Scot was involved in a number of remarkable things.

Fleming was chief engineer of the Canadian Pacific Railway and surveyed the first rail route across Canada, designed their first postage stamp, and successfully championed the Trans-Pacific telegraph cable that was put in from Vancouver to Australia.

With the introduction of railways, it became highly inconvenient and inefficient to work to a local time. Travelling over any distance by train would involve resetting your watch to local clocks or carrying a number of watches. It made planning train journeys difficult and ineffective, and gave the stationmaster a real headache when dealing with train schedules in local time.

Fleming saw that this couldn’t work and devised a universal twenty-four hour clock, dividing the world map into twenty-four time zones.

No comments:

Post a Comment